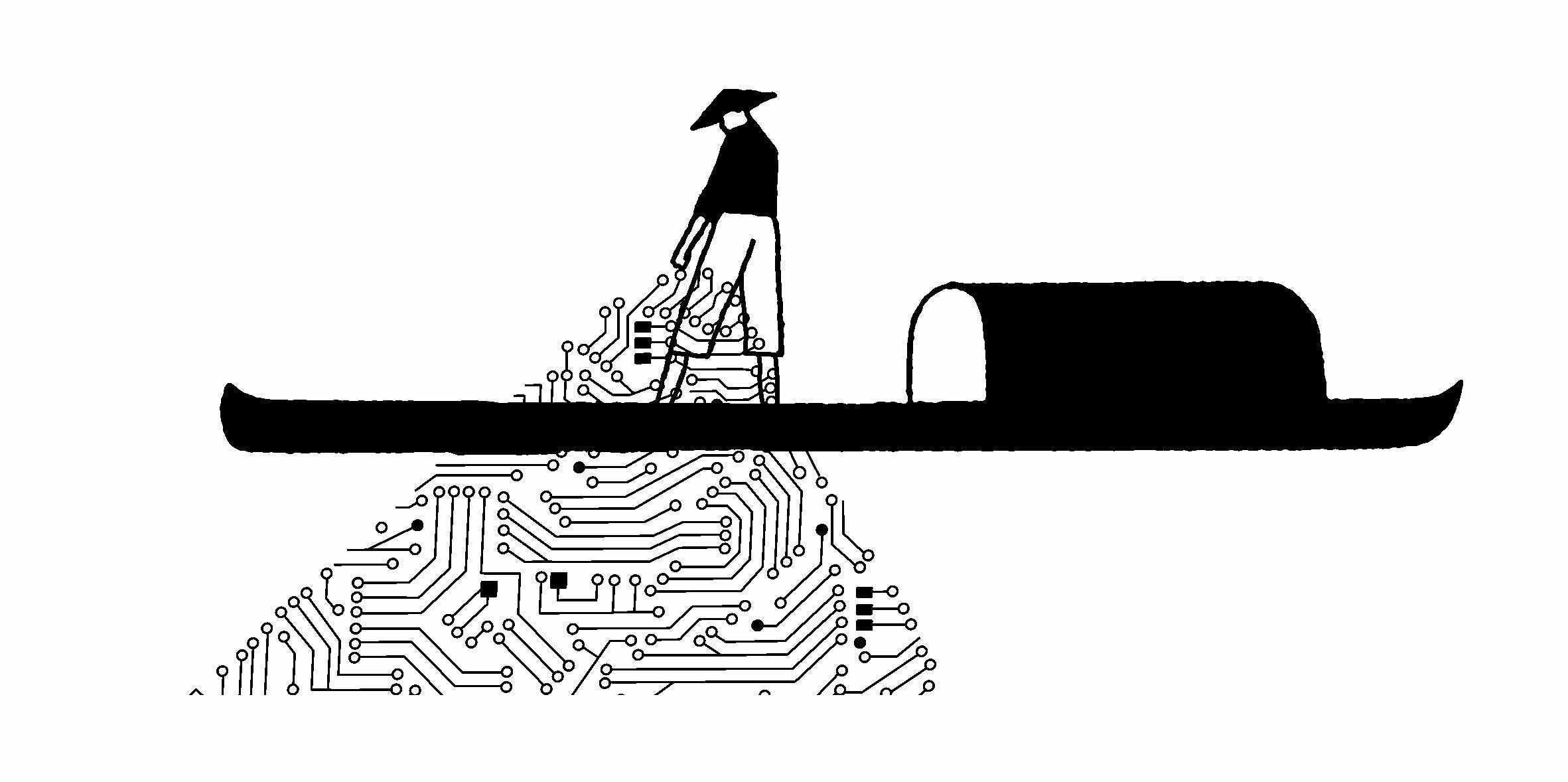

Over the past five or six years, China’s state-backed global information strategy, which once seemed incapable of exerting significant influence internationally, has been radically overhauled and expanded. This shift comes at a time when many democracies’ media outlets are consolidating, due to financial pressures. It also comes at a time when, within China, the Xi Jinping administration is consolidating its own power and creating a repressed and somewhat closed national internet – one that favors Chinese state platforms, and that often does not allow sensitive information to flow into the country.

Under Xi, China’s state-led global information offensive now includes a vast range of tools. These include: modernizing and expanding China’s international state media outlets, like television channel cgtn and newswire Xinhua, and trying to make an international audience view them as highly credible sources; using pro-China businesspeople to buy up media outlets in other countries, quietly purchasing radio, broadcast, and social media outlets from the United States to Australia; training journalists from many nations as part of a global soft power project launched by Beijing in 2012; attempting to control a range of internet platforms outside China by facilitating the spread of state-owned messaging and social media apps while also creating a Chinese model of the internet at home, for others to copy. Beijing’s information tools also include using diplomats’ influence to repress negative coverage of China in the Chinese-language press elsewhere and using pro-China student groups abroad to pressure university media outlets’ coverage of China on campuses.

THE INFORMATION BATTLE FOR SOFT POWER. Overall, the state funding for China’s expanded media and soft power offensive has been estimated at as much as $20 billion annually. This would be larger than any other country’s state media campaign – even bigger than the budget of Al Jazeera, Qatar’s globally influential news giant. It is vastly larger than the budgets of the United States’ global government-funded broadcasting efforts, or those of France or even Russia.

To cite just one example of the growth of China’s state media outlets, let us consider Xinhua. Just ten years ago, the news agency was not picked up in most newspapers and online outlets outside of China. But in the past two years, Xinhua has been aggressively signing content sharing deals with major media outlets in many nations. Now, Xinhua content is increasingly featured in prominent publications in Asia, Africa and, increasingly, Europe. Running in major outlets, Xinhua’s stories can appear to a reader similar to content from Reuters, the Associated Press, or Bloomberg. Stories from all these agencies might appear on the same page, though Xinhua is a state news agency. Indeed, the us China Economic and Security Review Commission, which monitors China’s information and media efforts, has warned that Xinhua is far from a normal newswire. In fact, the Commission has warned that Xinhua employs intelligence agents among its reporters, and other analysts have suggested that Xinhua regularly uses reporters as spies.

This information strategy coincides with Xi becoming the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao. Xi is the only one since Mao to truly develop a cult of personality around himself. It also comes at a time when Russia has demonstrated a model of an authoritarian state using information operations to bolster Moscow’s regional influence in Europe and, in many cases, successfully sow distrust within Central and Western European democracies of their own political systems. Although China appears more interested in using its information strategy to portray positive narratives about Beijing and the China model of development (rather than using information to undermine democracies and cause chaos), in the long run Beijing could use their information network and skills to highlight democracy’s weaknesses to foreign audiences.

The media expansion also fits into Xi Jinping’s desire to expand China’s political influence in other nations, using a range of tactics that can be classified as more traditional. These traditional interference strategies – which have been ramped up intensively under Xi – include using funds to influence politicians and political parties in other countries, trying to influence ethnic Chinese associations in other countries, and engaging in cultural and educational soft power efforts.

China’s expanded information battle could have significantly negative implications for democracy and for rights around the world. It could also have a significant effect on the strategic and economic interests of democracies, if China, like Russia, gains a major tool of leverage inside their political systems and societies. However, if China pushes its global information strategy too hard, it could backfire against Beijing. Too much control of the internet at home could lead foreign technology firms to pull their investments out of China, and too much information warfare abroad could lead to a backlash by foreign countries, making it harder for Chinese tech giants like Alibaba, Tencent, Huawei, and others to pursue their global expansion plans.

WHY CHINA WANTS TO DOMINATE INFORMATION. Indeed, under the Xi administration, China has embarked on a concerted strategy to expand its influence over information in many nations, with the effort beginning in the Asia-Pacific. This information strategy is increasingly being applied in Europe, Africa, Latin America, and North America. Xi’s administration has several reasons for engaging in this information battle. For one, it is part of a broader effort to bolster China’s influence in other countries’ domestic politics — a major shift away from pre-Xi Chinese administrations that did not try to openly wield influence in foreign nations. In fact, according to recent reports in the Financial Times and other outlets, Xi has specifically tasked the United Front Work Department, an organ of the Communist Party, to boost Beijing’s influence in foreign societies and politics. This influence campaign is often easier in democracies, which are relatively open societies, and thus have political systems and media markets that can be more easily penetrated.

China also appears to want to control a range of platforms for information, as well as producing information itself. At its 2017 World Internet Conference (China’s big annual showcase for its approach to the internet and technology in general), Beijing demonstrated the power that China could wield over the internet and related companies. China’s $3 trillion digital economy and huge consumer market makes it a highly influential actor when it comes to global technology companies and to internet standards. A parade of top tech luminaries came to the summit, even though China has essentially blocked Facebook since 2009 and has severely limited Apple’s activities there. Nevertheless, Apple head Tim Cook spoke at the Conference, Google ceo Sundar Pichai also attended it, and Facebook leaders continue to aggressively court the Xi administration. Although China usually blocks reams of foreign information, foreign websites, and foreign social media companies, during the Conference Beijing allowed a completely free internet… just for conference attendees.

Chinese leaders further used the World Internet Conference to explain that they understand how the internet is critical to Beijing maintaining high growth rates and raising the value of its economy. They may even understand that too much control of the internet and social media could undermine that growth. Yet Chinese leaders also utilized their forum to demonstrate that China is not going to drastically open up its internet: it wants a great deal more say in how global internet standards and rules are adopted and applied.

The Xi administration has a plan to boost domestic Chinese content in many cutting-edge it industries – a plan that many foreign companies fear will make it even harder for them to compete for the eyeballs and money of Chinese users and consumers. To accomplish this plan, Beijing is unlikely to allow much greater foreign investment in its internet and social media sectors – but yet must somehow still portray China as open to innovation and new technology.

China, unlike Russia, also wants to foster an international narrative of its state as a developmental model. Few other states would look to Russia as a model of development. After all, Russia is a country dominated by oligarchs; it has few truly innovative companies, an economy dependent on oil and other natural resources, and no clear plan to expand innovation in next-generation industries like renewable energy, artificial intelligence or self-driving cars.

But China, especially under Xi, promotes itself as a model of development for other countries. To other states, this model can seem quite alluring as China maintains high growth and increasingly dominates high-tech industries like artificial intelligence and supercomputing. In fact, China is poised to dominate artificial intelligence in the coming decades, and it has already moved beyond American firms in some aspects of artificial intelligence. Beijing is focused, more than Russia, on using its information strategy to quash criticism of Beijing around the world – and to promote this narrative of Beijing as a model and a world leader, in an effort to eventually replace an inward-looking United States.

WHY IT MATTERS. As China’s information strategy expands, it could have major consequences for rights and democracy, for the global media, and for how the entire internet is managed. It may also give Beijing more leverage over other states, in the event of any economic or strategic battles.

By expanding and promoting its state media, China could divert viewers from media outlets that provide more balanced coverage of current affairs, leaving them watching cgtn or reading Xinhua, and not understanding that these state publications are seriously biased. This shift toward more people reading and watching Chinese state content around the world could, in the long term, provide Beijing with leverage in many nations’ domestic politics. This is a kind of tool Moscow has already utilized in Europe to flood local news environments with pro-Moscow coverage and to shift some European citizens’ views of relations with Russia and even of their own European politicians.

Indeed, China could use its increasingly powerful state-backed information outlets to sow confusion about important policy issues of relevance to Beijing, to undermine the authority of democratic politicians, and to promote conflict within democratic societies. In a case of economic or strategic conflict, China could utilize its expanded media presence — and its increasing control of media platforms — to undermine public support for leaders of countries at economic or strategic loggerheads with Beijing.

Beijing also could use information to promote a more positive shift in coverage of China globally. A shift in media portrayals of Beijing will make it easier for China to pursue a wide range of foreign policies, including many contrary to the interests of the United States and its partners in Asia. To take two examples: in Indonesia and Thailand, where Chinese state media is expanding, China’s increasingly positive public image in these nations (due at least in part to media coverage), makes it easier for Beijing to complete its policy objectives.

The expanded information campaign also will give Beijing significantly more powerful tools to buttress China’s closest strategic partners. In Asia, this often means authoritarian regimes. Beijing is already taking this approach in Southeast Asia. For instance, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen recently launched the broadest crackdown on Cambodia’s opposition in nearly two decades and during this repression, Xinhua, as well as smaller Chinese media outlets with a social media presence in Cambodia, aggressively backed Hun Sen. As China’s media toolkit grows larger, Beijing’s state-linked outlets could launch such campaigns in a much broader range of countries, helping prop up Beijing’s favored leaders. In addition, China could use its media offensive to undermine specific democratic leaders in countries with which it has disputes.

Even when China is not burnishing its image, it can use its media offensive to silence negative global news coverage of its foreign policies, its domestic economic policies, and its growing suppression of rights at home. Silencing international coverage that reflects poorly on China has been accompanied in recent years by an increasing crackdown on Chinese reporters. Even groundbreaking domestic Chinese outlets, like the famous Beijing-based financial publication Caijin or the Hong Kong-based newspaper South China Morning Post, have felt Beijing’s wrath.

In recent years, it has been foreign outlets based outside China — ones with sources inside the country or with a handful of credentialed reporters — who have provided important information, both to the world at large but also to the Chinese people. They have covered stories on corruption, political repression and religious repression inside the People’s Republic. The New York Times, for instance, has revealed stories ranging from the vast amounts of wealth amassed by the families of top Chinese leaders to the opaque ways in which big Chinese firm (like hna Group) have structured their corporations, even as they buy up stakes in the biggest European and American companies. Should Beijing’s information tactics succeed in inhibiting critical coverage even by foreign outlets based outside China, it would naturally help further entrench highly authoritarian rule in China.

Furthermore, this influence increasingly extends down into university campuses and small publications in Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and elsewhere. In Australia in October 2017, for instance, the head of the country’s top intelligence agency, Duncan Lewis, warned that China was wielding influence in Australian universities, whether by monitoring Chinese nationals on university campuses, trying to shape campus media, or funding educational institutions and think tanks linked to universities. This influence could reshape – and silence – campus intellectual discussion about Chinese policies.

Finally, as mentioned earlier, the plan to dramatically expand China’s global information efforts comes alongside the most intensive campaign in decades by Beijing to influence other nations’ domestic politics in more traditional ways. Traditional interference has been accomplished via efforts ranging from money funneled to foreign politicians who take policy positions sympathetic to Beijing, to efforts to prod ethnic Chinese organizations in foreign countries to take a pro-China line, to donations to educational institutions in foreign states. Mixed with more novel information warfare, such influence is bound to increase.

In New Zealand, University of Canterbury professor Anne-Marie Brady has extensively documented Beijing’s expanded efforts at traditional influence. She has noted that China has worked to control its ethnic associations in New Zealand, lavishly funded a range of New Zealand educational institutions and think tanks, and may even have placed people with links to Chinese intelligence in the New Zealand parliament. Brady notes that “after Premier Le Keqiang visited New Zealand in 2017, a Chinese diplomat favorably (in private) compared New Zealand-China relations to the level of closeness China had with Albania in the early 1960s.” But New Zealand and Australia are not alone: these traditional influence campaigns are also increasingly obvious in other parts of Asia, as well as in Europe, Africa, and North America.

THE RESULTS. Beijing’s increasingly assertive approach to information – controlling it at home while engaging in an information offensive abroad – could well work for the Xi Jinping administration. In the long run, it may be able to use its information offensive to shape narratives in the global media about China and China’s policies. It could even use its state-backed information efforts to undermine critics abroad while bolstering leaders who favor the People’s Republic. As China’s economy grows – and if the United States continues to abdicate its role as a world leader – China may also be better placed to set the rules and standards for the internet worldwide. Finally, within the country, the Xi administration might be able to walk the fine line of its choosing, keeping its citizens from accessing and discussing much content critical of Xi or the Party, while also promoting innovation and growth in cutting-edge, internet-centered industries.

However, the strategy could also backfire. Despite China’s enormous consumer market for all manner of internet services, foreign companies’ patience with Beijing’s censorship and attempts to tilt the playing field for Chinese firms, could eventually wear thin. Restrictions on foreign investors and the demand that technology companies transfer intellectual property to Chinese partners has rendered many cutting-edge it start-ups in Europe and North America shy about trying to expand into the Asian giant’s market. Although Facebook and Apple have not given up yet, other major tech companies have.

Even some large Chinese technology companies have bristled at restrictions, complaining that they stifle innovation and make it hard for them to attract top talent. They also complain about how often – and seemingly with no warning – China changes its rules about the internet. This makes it hard even for Chinese companies to keep up.

Meanwhile, other countries could retaliate if China expands its information warfare and if the country is seen as increasingly interfering in other nations’ politics and societies. Already, the United States and others are pushing back at China’s information offensive and influence game. The Trump administration is increasing its trade pressure and launching investigations about intellectual property violations. In Australia, the Malcolm Turnbull government has responded to media reports of Chinese influence with new laws on foreign donations and heightened government scrutiny of Chinese investments in national infrastructure projects. Australia’s top intelligence agency, meanwhile, has publicly warned Australians of China’s growing influence, and relations between Canberra and Beijing are growing increasingly frosty.

In the end, China’s information warfare could lead to such blowback that Beijing might have to rethink its entire global information strategy.