Toward a more balanced global growth?

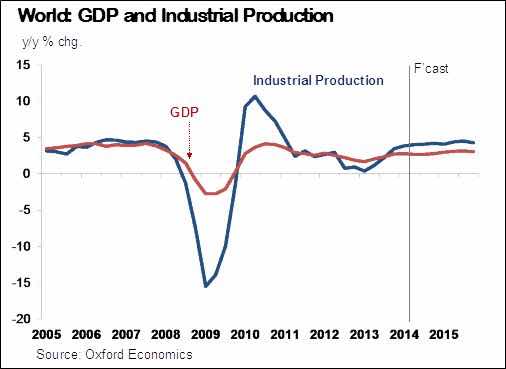

Six years after the start of the Great Recession of 2008-09, the outlook for the world economy now looks relatively optimistic, albeit amid some new risks and challenges.

Following years of balance sheet adjustment and policymakers internalizing the lessons of the crisis, advanced economies appear equipped to move on. The process of “deleveraging” in these economies, although patchy, has been rather successful and the ghost of a systemic collapse, materializing from the banking sector or from sovereign entities, is for the time being behind us. At the same time, while most emerging markets are slowing down from the substantial growth rates enjoyed in the last decade, their pace of expansion is on average still robust.

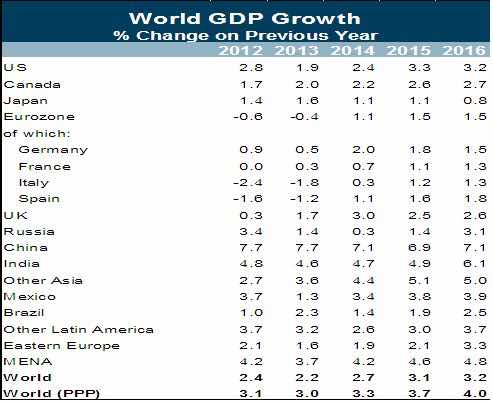

Overall global GDP growth (at Purchasing Power Parities) is now expected to pick up from 3% in 2013, to 3.3% in 2014 with an additional improvement to 3.7% in 2015. The outlook reflects better growth prospects in the advanced economies and a slowdown in the emerging markets.

GDP Growth in Advanced and Emerging Economies

Official data for the last several months show that recovery is under way in most OECD countries. In the US, while GDP data for the first quarter were disappointing (revised downwards several times to -2.9%) due to unusually bad weather conditions, PMI indices continue to point to an improvement in economic activity. At the same time, unemployment data show that claims for unemployment are at their lowest since 2007, allowing for better consumer expenditure and relieving some pressure on government finances. In the context of some uncertainties with respect to a better than expected labor market, the Federal Reserve is likely to proceed with its “tapering” schedule, leaving interest rates unchanged well into 2015. US GDP growth is now likely to show a significant rebound in the second quarter, and overall annual growth should exceed 2% in 2014 and increase to well over 3% in 2015.

In Japan, the so-called Abenomics has obtained some significant results in raising inflation expectations, with prices rising almost 2% in early 2014, and with the Yen devalued as a consequence of the massive injection of liquidity by the Bank of Japan (Japanese Quantitative Easing has been so far twice the size of that of the US relative to their respective GDPs and is likely to increase further). At the same time, the combination of expansionary fiscal and monetary policy (the latter allowing for better credit conditions), has managed to lift business and consumer expectations steadily into positive territory. However, the uncertainties regarding the implementation of the structural reforms, initially promised as the “third arrow” of Abenomics are affecting negatively Japanese prospects and the Tankan confidence indicators have started retreating.

The picture for emerging markets is varied, but still positive overall. Ben Bernanke’s May 2013 announcement that the Fed would start its tapering process to reduce its Quantitative Easing policy, exposed the weakness of several emerging economies. The ensuing flight to quality of financial investors – away from emerging markets – hit countries with poor external balances and/or critical government fiscal positions, such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Turkey, just to name the most relevant for the global economy. In the second half of 2013, these countries saw their currencies devalue quickly with a negative impact on inflation and have had to implement quick financial adjustments, typically raising interest rates and adopting measures aimed at cutting public deficits. Such developments raised questions over the global systemic risk which could derive from the continued stress of large emerging economies. The Fed however stuck to its tapering schedule which started at the beginning of 2014 and reaffirmed its “forward guidance” of low rates for an extended period of time. This allowed for an improvement in the financial conditions of most emerging markets, and today the relief appears to be reassuring that a systemic crisis is unlikely to originate from emerging economies, which on average will continue to enjoy interesting growth rates.

The risks to this relatively optimistic picture come mainly from two areas: China and Europe.

China is going through a process geared to developing a more balanced economic activity, in line with the plan of increasing consumers’ demand at the expense of investment and net exports. As a result Chinese growth is expected to slow down in 2014 and beyond to levels around or below 7% per year. The re-adjustment process is also made more complicated by the rapid credit growth in recent years and by the current state of the financial sector, with the presence of a large and largely unregulated shadow banking system to cast doubts on the sustainability of the Chinese non-financial corporate debt (almost twice the size of that of the US, considering their respective levels of GDP). According to Oxford Economics simulations, a crisis in the Chinese banking sector could plunge the country into a severe economic slowdown, with just 2% growth in 2015, paving the way for social unrest and possibly even political upheaval. The repercussions on the global economy would be significant with world GDP growth falling by 2% with respect to the baseline. However, some structural features of the Chinese economy, such as reserves of $3.6trn, low government debt and support for growth coming from the availability of vast labor resources, give Chinese policy makers enough tools to manage their banking system problems.

At this stage, Europe is the most likely candidate to win the title of “sick man” of the world economy. While the major risk of a euro break up appears to be behind us, worryingly high unemployment and persistent low growth define the prevailing short to medium term scenario for the area. After several years fighting against excessive fiscal imbalances of peripheral countries with little support from monetary policy, the split between the Eurozone core economies and the remaining countries is still remarkable. In particular, Germany seems to be taking on the role of bright star of the continent, with an external surplus of over 7% of GDP, a balanced fiscal position, unemployment under control and a solid industry structure. The other side of the coin is unemployment and still high public deficits in the peripheral countries, with insufficient growth to address either problem.

The key risk for Europe now lies in deflation –close to zero or even negative price changes. Deflation brings with it a number of unpleasant consequences, for example the postponement of purchase decisions, the increased difficulty to repay debt (be it private or public), sluggish growth and above all limited room for policy action, as interest rates have an insurmountable below-zero threshold. As a consequence, for policy makers deflation presents an additional challenge – it needs to be anticipated. This challenge is particularly daunting for the ECB, for two reasons. One is that the philosophy which has historically guided ECB monetary policy (and the Bundesbank before the ECB) is one of fighting inflation and the central bank has been culturally against unorthodox measures such as Quantitative Easing. The other is due to the divergences in price behavior across the different Eurozone countries: this renders what is an expansionary monetary policy for one country, a restrictive one for another.

In early June the ECB announced a package of measures aimed at easing monetary conditions in the Eurozone – including negative interest rates on banks’ excess reserves, a cut in the repo rate and new long-term refinancing facilities linked to lending to the business sector. Many analysts considered these moves as overdue (especially since most of the action will take place over the next several quarters), in light of average Eurozone inflation hovering at just 0.5% and zero or negative GDP growth in key countries such as France and Italy in the first quarter of 2014. The overall pattern of “surprises” in Eurozone economic data has become heavily skewed to the negative over recent weeks and the forecast for Eurozone GDP growth in 2014 has been generally revised downwards, close to 1%. The question is now – is it too late to reverse the trend and put Europe back on a solid recovery trajectory?