The changing China-Europe geo-economic relationship: a wake-up call for the EU

Italy´s decision to sign – as the first G7 country to do so – a Memorandum of Understanding with China (in the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative – BRI) has spurred much criticism, both among European partners and in Washington. The timing is particularly awkward, as relations between Beijing and the West are growing increasingly tense. Whatever the logic of Rome’s initiative and the understandable desire to attract Chinese investments in infrastructure, it has not given consideration to the transformations taking place in the Chinese-European relationship as well as Italy´s limited strategic economic leverage both vis-vis Beijing and other European countries, particularly Germany.

In fact, along with the geopolitical and security implications for the link to the United States, Italy´s government seems to have ignored three key factors: China´s evolving attitude toward financial commitments abroad, the fundamentally geo-economic nature of the BRI, as well as the country´s interdependence with Europe´s and Germany´s supply and value chains.

Xi Jinping´s European tour occurs at a difficult moment for the Chinese leader, as he is trying to respond to both mounting Western criticism of the Belt and Road Initiative and to pressures at home to maintain a sustainable growth rate in the face of a (relatively) slowing economy, hit by the combined effect of Trump´s trade war, rising concerns over capital outflow, and the continued growth of bad debt.

Western criticism of “neocolonialism” and of “debt trap” diplomacy, has become particularly loud after China seized control over the key Sri Lankian Port of Hambantota following the country´s default on its debt. Meanwhile, worsening economic conditions at home call for a more “commercial” approach to outward investments. Considering the mounting bad-debt of companies and local authorities, outward investments should be either more commercially sustainable, or guaranteed by valuable collaterals, or reduced in size.

Consequently, to counter criticism and rationalize its investment policy, China has recently started recalibrating its financial commitments in weaker economies in Eurasia and Africa. Particularly in Africa, Beijing has increased the volume of grants and non-interest-bearing loans, but it also introduced more restrictive criteria for commercial loans while it has accepted that some loans for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor(CPEC) will be redirected to non-CPEC related projects.

This recalibration is becoming visible also in Europe´s advanced economies, where Beijing seems tempted to follow a more cautious path for its financial commitments, while its traditional bilateral approach stimulates attempts at greater European coordination.

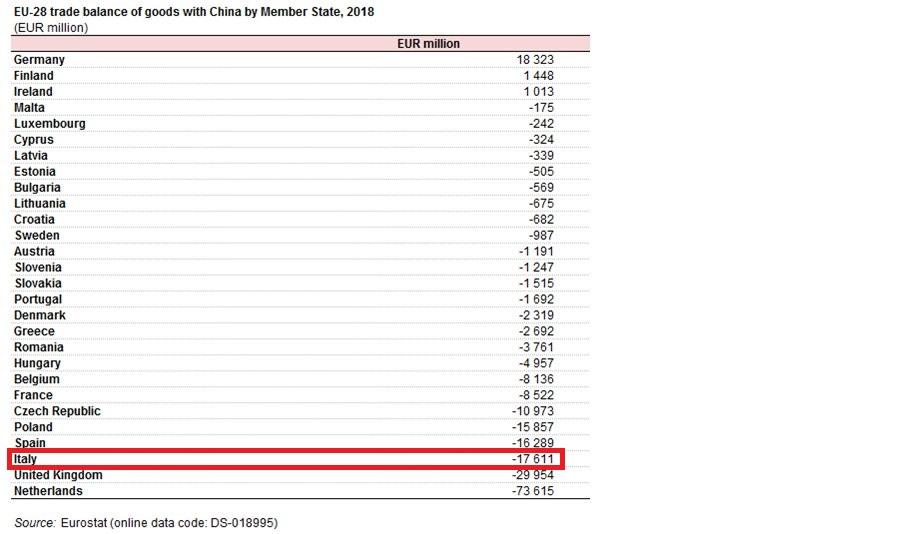

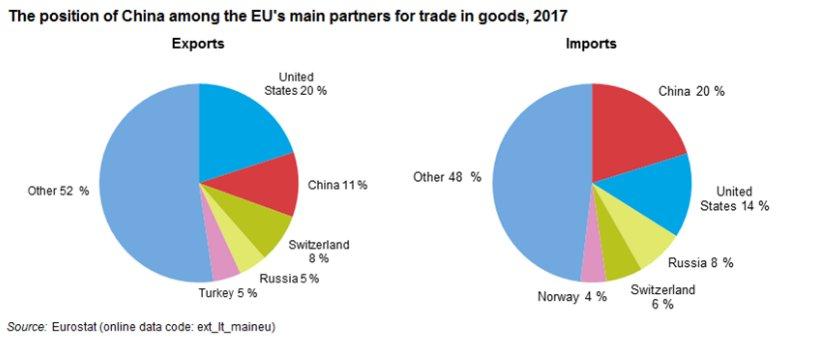

Europe remains not only China’s second trade partner but also an attractive destination for investments in cutting edge technologies and infrastructure (Chinese FDI reached almost 18 Billion USD in 2018), a core market for its goods and, increasingly, a production platform for private and state companies as part of the Belt and Road Initiative and the “Made in China 2025” strategy.

However, China´s investments in critical infrastructure, particularly in the Western Balkans and in Central Eastern European countries, are increasingly under scrutiny, as countries like Poland or Czech Republic start lamenting scarce results in terms of more balanced trade relations. Recently, critics of cyber espionage related to the planned investments by Chinese tech giants like Huawei and ZTE in Europe´s next generation of telecommunications networks (5G) have increased the pressure on Beijing. As a result, while key European countries have resisted Washington´s pressure to ban Chinese technology, China´s investment behavior is increasingly perceived as predatory and designed to acquire geo-economic and geopolitical influence. By approaching single EU-members on a bilateral basis, Beijing´s strategy is considered part of a mounting systemic competition between a coherent, sino-centric Eurasian-Pacific space and an increasingly dispersed and fragmented West.

Against this backdrop, the EU has slowly toughened its stance toward China to show greater political cohesion. On March 5th the EU approved a new screening mechanism explicitly aimed at coordinating national efforts to control and eventually block Chinese investments in critical, security-relevant infrastructure. Moreover, the EU Commission has released an EUChina Strategy draft in which for the first time Beijing is defined as a “systemic strategic competitor”.

Pointedly, the EU Council has discussed this document on the same day that Xi landed in Italy, and the planned bilateral meeting between the Cinese President and Emmanuel Macron has been extended to Angela Merkel and Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker.

A mix of more rigid EU regulations and Beijing’s stricter controls over capital outflows have already led to a decrease in the level of investments in Europe. In 2018 they declined by 40% on 2017. China seems indeed increasingly aware that it needs to both show political willingness to adapt the BRI to politically less favorable conditions and take in greater consideration returns and commercial viability of its financial commitments.

Against this background, Beijing’s specific interest in the Italian MoU comes in sharper relief.

President Xi wanted a diplomatic success to polish up the BRI´s brand and increase its attractiveness both in Europe and across Eurasia, without making large financial commitments. The MoU serves this scope nicely.

Conversely, it will be harder for Italy to reap major long term benefits, especially as a potential logistic and transport hub based on the ports of Genoa and Trieste.

In the past 10 years Europe´s manufacturing basis has shifted from West to East. The new manufacturing core of the continent is now located in Central-Eastern Europe and centered on Germany´s supply and value chains. This space is the major source of Europe´s export towards Eurasian, Asian and Chinese markets and China´s main geo-economic focus in Europe. It includes some EU-central-eastern European members and few Italian regions in the north and north-east but excludes the remaining regions of western, central and southern Italy.

For its part, China´s investment strategy in Mediterranean ports is more centrifugal than centripetal, as it tends to functionally divide the eastern from the western and the southern from the northern Mediterranean, according to the spaces and markets it targets. This is testified by various participations in different relevant ports across the Mediterranean. However, as Beijing clearly privileges the eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans as a gateway to the Central-Eastern European manufacturing core, only Trieste is well suited to serve this function. China´s potential investment in the port of Genoa, due to limited hinterland connections and infrastructural shortcoming, will focus more on touristic ship-yarding and less on intra-European container traffic.

Under these circumstances, to realistically and sustainably profit from stronger ties with Beijing and advance its legitimate national interest, Rome should get more realistic about its assets, prioritize its action both sectoral and geographically, as well as seek greater political, strategic, diplomatic and economic coordination with European partners, first and foremost with Berlin in the Eastern Adriatic.

Moreover, Berlin would be well advised to to more strongly engage Rome in the ongoing strategic rebalancing Europe is pursing vis-a-vis China, and on the emerging Eurasian dimension of EU foreign economic policy. In the evolving intra-European and global context, all EU members should firmly embed their legitimate national aspirations and interests in a strong continental consensus: close coordination and strategic thinking are absolutely essential in tackling the Chinese challenge and turning the risks in opportunities.