Facing the Transatlantic truth: divergent US and European security interests

Media reports that President Donald Trump discussed the possibility of US withdrawal from NATO with other officials on several occasions in 2018 have produced enhanced anxiety among Alliance partisans on both sides of the Atlantic. But Trump is hardly alone in suggesting that a new transatlantic security relationship may be needed.

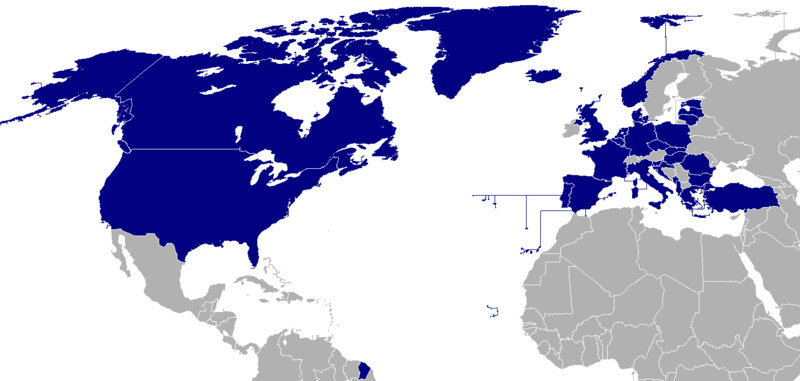

NATO’s Cold War mission receded into history more than a quarter century ago, and there is growing awareness that while America and Europe have important security interests in common, those interests are far from being congruent. Not all security problems impact all portions of the democratic West equally. It is irrational to assume that disorders in the Balkans, North Africa, or elsewhere on Europe’s periphery should be as important to the United States as they are to the European Union countries. Likewise, it is not reasonable to believe that EU members should be as concerned as the United States about problems in Central America, the Caribbean, or Venezuela.

Indeed, expressions of that realization surfaced during the first post-Cold War decade – and did so at least as much in Europe as in America. As NATO increasingly pursued “out of area” missions during the 1990s and early 2000s, some NATO traditionalists in Europe became very uneasy about the implications for the Continent. Comments like those of Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who suggested that NATO become a force for peace “from the Middle East to Central Africa,” strengthened such apprehension. Albright’s former Clinton administration colleagues Warren Christopher and William Perry went even further than she did, urging that the Alliance be an instrument for the projection of force anywhere in the world the West’s “collective interests” were threatened.

French Foreign Minister Hubert Vedrine cautioned against that approach, warning that it ran the risk “of diluting the alliance”. Without a reasonably tight geographic focus, he believed, NATO could become a global crusader, endangering European interests in remote arenas. Spanish Foreign Minister Abel Matutes was even more specific that Europe did not have a stake in every geopolitical problem the United States might want to address somewhere else in the world. He stressed that what happens “8,000 kilometers from us – in Korea, for example . . . cannot be considered a threat to our security.” Vedrine echoed his point, saying that NATO “is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, not the North Pacific”. Such comments indicated a graphic recognition that American and European interests were distinct and separable, not identical or even always compatible.

Henry Kissinger, Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer, and other prominent “NATO traditionalists” also made that important distinction from the American side two decades ago. Krauthammer was caustic about the increasing focus of the “new NATO” on out-of-area missions. “For the clever young thinkers of the [Clinton] administration,” he observed sarcastically, the Alliance’s traditional deterrence mission apparently was “too boring”. He saw them as wanting to refashion NATO as “a robust, restless alliance ready to throw its weight around outside its own borders to impose order and goodness”. Kissinger shared that concern. “Kosovo is no more a threat to America than Haiti is to Europe—and we never asked for help there”. He worried about blurring such important differences and having Washington responsible for resolving every manner of parochial problem in or near Europe.

Such concerns were warranted. The United States is still entangled in the Balkans, trying to help resolve quarrels between Serbia and now-independent Kosovo. Washington even dispatched a 500-person troop contingent in 2017 to bolster the international peacekeeping force there when tensions flared sharply. A major reason that Barack Obama’s administration launched a regime-change war in Libya was because of pressure from key NATO allies, especially Britain and France. The US government also is on the front lines of dealing with Russian-Ukrainian and Russian-Georgian disputes. US leaders still seem to make no meaningful distinction between the interests of the United States and Europe.

That approach is both illogical and excessively burdensome. A new generation of critics is renewing the argument that NATO shows serious signs of obsolescence and that U.S. and European interests are not identical. Public opinion surveys also confirm that there are substantial and widening differences between American and European perspectives on a wide range of foreign policy issues. Such a realization might well have taken root and grown after the first round of dissent that surfaced in the late 1990s, but the 9-11 attacks and the onset of the so-called war on terror temporarily reinforced a sense of transatlantic solidarity, thereby stifling debate and needed policy changes.

Creating a strong European security organization to handle purely European contingencies makes sense for both sides. US leaders should encourage European ambitions for an independent security capability, not blindly emulate previous administrations and seek to sabotage those ambitions. Such an organization ought to take primary responsibility for the Continent’s security affairs and for addressing problems on Europe’s periphery. A mechanism for transatlantic security cooperation should be reserved for serious threats that menace both the United States and Europe.