Understanding the internal conflict in Cameroon: a question of negligence

With so many unresolved conflicts in the region, the international community is paying little attention to the Cameroon crisis; and yet, the dire battle between the government and separatists risks to escalate into a civil war. Although Cameroon is often looked at as one of the healthiest African economies (its GDP was growing by 4.7% in 2016), it contains the seeds of internal conflicts, which now risk to sprout like never before in its history.

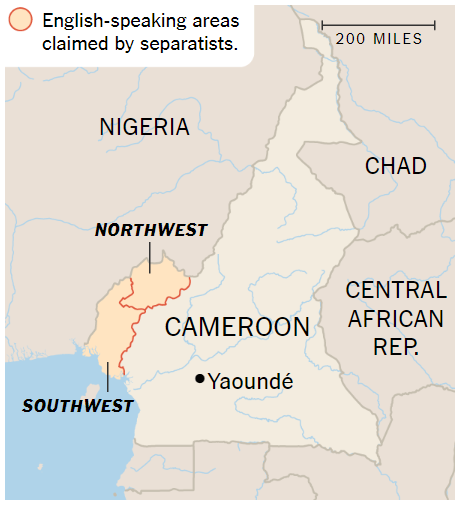

As the conflict is rooted in the colonial history of the country, a step back is cardinal. After World War I, Cameroon passed from being subjugated by Germany to being held a colony of both France and the UK. It even has two different spellings, according to the area and the language: Cameroon for English, and Cameroun for France. However, if on one hand France embedded the territory into its economic model and system, the British did not, and governed instead from the neighboring Nigeria, neglecting what was considered a secondary province. When the country finally gained independence in 1960, such a picture was already crystalized: the French-speaking territories could look forward to their development, whereas the western provinces were held back by poverty.

This negligence and malpractice is now regarded as one of the main factors that caused the underdevelopment of the formerly-British areas. The separation is not based on ethnicity like in many other areas of the continent, but for as much as this divide is blurrier than it used to be, the population still resents the central government and blames it for its hardship. In fact, this conflict is less about language and ethnicity than it is about being abandoned: only about a fifth of the population in the two Western provinces is genuinely Anglophone, but all experience impoverishment. The economic gap kept growing since the independence, and even nowadays the funds allocated for regional development by the central government are largely unbalanced.

The idea that Anglophone Cameroon (sometimes referred to as “Southern Cameroon) should have stayed independent has been crossing activists’ minds for decades. Because of this, it is relatively arduous to situate in time the exact moment when tensions arose and assumed the connotations of a real crisis. Tumultuous moments broke out already in 2016, when activists stepped up their campaign for independence and turned to violence and armed guerrilla warfare. The idea at the basis of their vindication is that President Paul Biya (who was elected in 1982 and is still in power) decided to venture on the development of other areas to the detriment of the western regions. Some noticed how the international contracts for agriculture, minerals and energy systematically privileges the northern and central regions. Or, to put it in another perspective, no matter the area of investment the spending of the government rarely favors the West. Yaoundé defended its budget allocations explaining how other regions – especially the central (with the capital Yaoundé) and two northern regions – represent more burning priorities. However, this triggered rage in the separatist movement.

The idea that Anglophone Cameroon (sometimes referred to as “Southern Cameroon) should have stayed independent has been crossing activists’ minds for decades. Because of this, it is relatively arduous to situate in time the exact moment when tensions arose and assumed the connotations of a real crisis. Tumultuous moments broke out already in 2016, when activists stepped up their campaign for independence and turned to violence and armed guerrilla warfare. The idea at the basis of their vindication is that President Paul Biya (who was elected in 1982 and is still in power) decided to venture on the development of other areas to the detriment of the western regions. Some noticed how the international contracts for agriculture, minerals and energy systematically privileges the northern and central regions. Or, to put it in another perspective, no matter the area of investment the spending of the government rarely favors the West. Yaoundé defended its budget allocations explaining how other regions – especially the central (with the capital Yaoundé) and two northern regions – represent more burning priorities. However, this triggered rage in the separatist movement.

For decades, the only true demand was federalism. Under this option, the rebels saw the opportunity of self-administration and of having their own government, perceiving Yaoundé’s as distant and unrepresentative of the needs of the poorest territories in the country. For years the central government has sought to undermine the autonomy and the identity of the western provinces, especially taking on language issues. Amid the many measures, in the fall of 2016 was the appointment of francophone judges in the western provinces – an action that caused thousands to demonstrate in the streets. The government sent the army and clashes with the people caused the first casualties. Escalating throughout 2017, the separatists – who call themselves “Amba Boys” – demanded full independence across villages, towns and cities, and then proclaimed the two provinces an independent state named Ambazonia. Some even painted their faces blue – the color of freedom, the main one of their new flag.

At the declaration of independence, tensions resolved to open conflict. Despite underrepresenting the crisis at the national level and within the democratic institutions, President Biya has resorted to violent methods locally. The escalation of violence by armed secessionists coincided with the militarization of the Southern Cameroons, an area where over two million people live in hardship. Since the first protests broke out, the government had cut the internet supply – and even phone lines – to prevent videos of dissent and abuses to spread out of Cameroon. In fact, only a few images of the conflict have leaked out. The military systematically fired on unarmed civilians, and guerrilla groups killed dozens of military. Many international NGOs report indiscriminate violence, methodical torture, rapes and abuses from both sides. Amnesty International has recently issued a report in which eyewitnesses account for hundreds of human rights violations for the first six months of 2018 alone. When asked to comment on specific episodes, colonels claim in regular podcasts that every conflict is necessarily grim, and that military action is in response to the killing by secessionists.

However, the outlines of the conflict are less defined than one would think and certainly hard to polarize. In rural areas for instance, separatists have turned on their own population as well: international reports claim that they have been vandalizing schools, burning down buildings and held hostage those who refused to take up an active role in the conflict. This clearly plays out well for the government, in that it managed to depict the separatists as unscrupulous individuals with a terrorist agenda. In this regard, it is interesting to notice how the rhetoric used seeks to confine the conflict to an internal dimension, thus sparing the international community the concern of an intervention.

The Defense Department has long accused separatists of “terrorism”, in a sinister allegory with the fresh threat of Boko Haram Islamist terrorism – that keeps menacing the country in the far north: a strategy that tries to take the political and economic claims out of the clashes, insisting solely on barbaric violence. On the other hand, secessionists are trying to appeal to neighboring countries, flagging the violence as conscious “genocide”. It is worthy of noticing that international operators are being cautious with this term, which could indeed trigger an international response: they assert that although the conflict has an ethno-linguistic shade, it is not the main divide; for however harsh the abuses of the military, they are not engaged in ethnic cleansing.

The conflict is of course resonating in neighboring countries, but the only one who’s seriously being affected is Nigeria – due to geographic proximity. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimates that more than 160,000 people have been internally displaced. Moreover, despite the efforts by Yaoundé to officially close the border with Nigeria, more than 21,000 have crossed it as refugees in the past months. In Nigeria, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) office launched a plea, fearing the worsening of their conditions and calling upon larger powers to pay attention to the conflict.

But the international community has been relatively quiet and remains non-partisan. While many diplomats have called for a simple ceasefire and the African Union remains silent, the US ambassador in Cameroon represents a notable exception. In a communiqué, Henry Peter. Barlerin went as far as accusing the government of target killings after being summoned by President Biya in a heated meeting that could have added a diplomatic incident to the conflict. The roots of the US hardness lie in the detention of the American-Cameroonian journalist Patrick Nganang, who was deemed persona non grata by the authorities after alleged accusations of human rights violations. In return, Cameroonian public officials have accused Ambassador Barlerin of funding the opposition (news steadily denied by the US administration). Despite peculiar situations, many Western countries fear the economic relations with Cameroon could be affected by the conflict as it exacerbates and therefore hesitate to take sides. The recent, controversial, reelection of President Biya, has only intensified tensions.

What is certain is that the conflict has rapidly spiraled into an economic crisis as well. Economy in the western region has plummeted, and trade with neighboring countries almost defaulted. Secessionists are said to be influencing trade with Nigeria on agricultural and textile goods, demanding payoffs as a newly-established custom. But this whole situation echoed of course in the national economy.

Even international financial institutions as influential as the IMF and the World Bank have warned the government: the crisis might cost dearly in terms of economic growth, forcing analysts to lower their expectations. Despite the efforts of the national government to minimize the range of the conflict, it is clear that international attention is growing. Analysts seem to agree that reforms and dialogue are much needed, or what once was negligence risks to turn into a dreadful civil war.