The sinister echoes of 1917 in today’s Russia

A century after Russia’s 1917 revolutions, the current government has hardly reflected on either event. As noted by American historian Chris Miller and others, the symbolism of the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and the October Bolshevik Revolution simply poses too many uncomfortable messages and parallels for Vladimir Putin and his government. Tellingly, the Russian government decided to commemorate the October Revolution, which led to the Soviet Union, by reenacting the 1941 revolutionary parade, which was held during World War II when German forces were approaching Moscow – a far safer historical memory.

The thought of these revolutions awakens awkward questions for the current Russian government. The February Revolution was a popular uprising that led to the deposition of the head of state and the end of the Russian Empire – neither a signal that the Russian government wants to acknowledge approvingly in an era of Color Revolutions, Maidans and the expansion of Russian foreign policy interests. The October Revolution does not pose a direct ideological problem as many people look at its Soviet legacy with nostalgia, but it too represents a violent change of government where the new leaders explicitly sought to undo the power of entrenched and corrupted elites – another uncomfortable reminder in today’s Russia.

Yet perhaps the most disturbing lesson from that era is that in the decade or so preceding the revolutions, the promise of political openness and competition following the 1905 Revolution dissipated. Over the four parliaments (Dumas) from 1905 to 1917, right-wing political forces demanding obedience to the Tzar and the state crowded out moderate voices and consigned the left to the street, where revolutionary activity eventually culminated into a challenge to state authority. The increasing lack of constraints permitted the leadership to take bolder and bolder foreign policy choices while not addressing social concerns – a combination that led to a war that turned unpopular and a widespread social revolution.

Over Vladimir Putin’s 18 years in power, political openness and competition have declined to the extent that opposition parties are explicitly loyal to Vladimir Putin. Moreover, the Russian parliament as a political institution is not only less politically competitive today than in the early 1990s, but far less than in the years leading to 1917. As was the case then, the lack of constraint from society via the legislature has produced an elite that allows the leader to expand foreign policy aims without regard for social concerns.

Open political competition began in Russia following the Revolution of 1905. The dangers of potentially losing his crown obliged Tzar Nicholas II to sign the October Manifesto, which set out real, albeit limited, political reforms. The intent was to bring the bourgeoisie into political life and accomplish in Russia what had been happening across the rest of Europe over the previous several decades. The Manifesto created a contemporary limited monarchy: a Duma, the Tzars continued rule but laws, such as those regarding freedom of speech, assembly, suffrage, and the formation of political parties, went through the Duma.

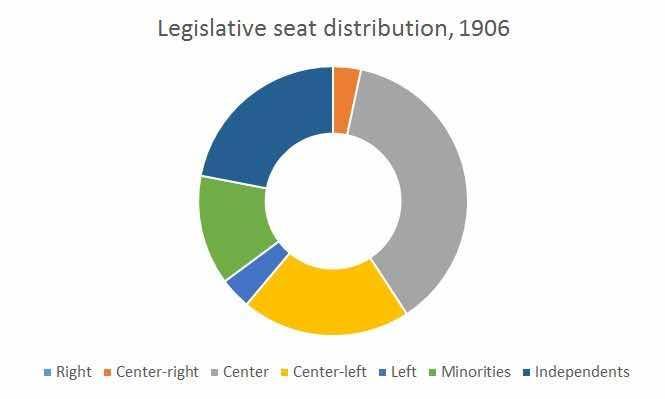

The latter political concession produced a number of parties that spanned the political spectrum, with nearly two-thirds of the representation spanning the center-left and center-right:

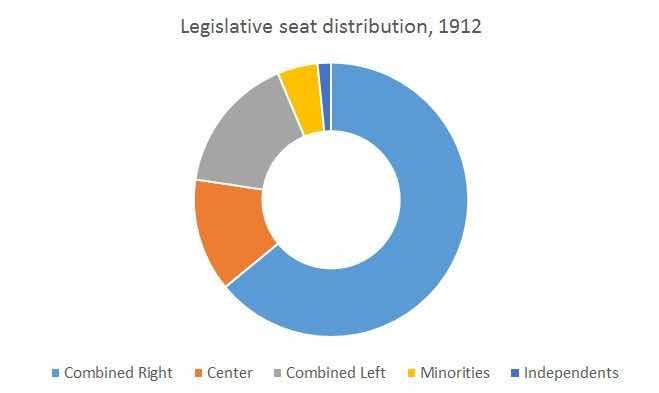

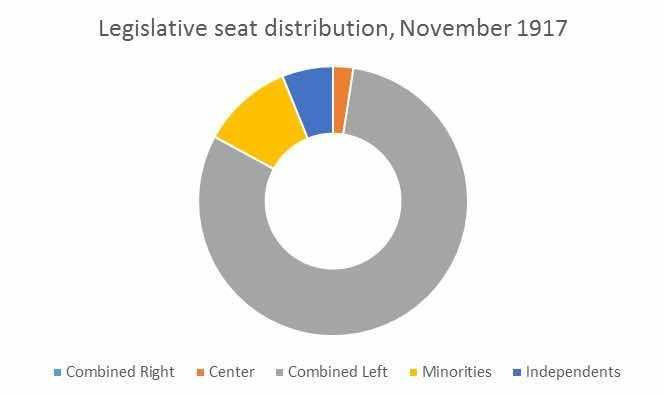

Tzar Nicholas II settled the 1905 Revolution by pledging more cooperative governance (at least somewhat) with society, but his inability to fulfill those pledges meant that moderate voices declined. From that relatively balanced legislature in the shadow of the first revolution, the space for political openness and competition eventually narrowed into a legislature dominated by those obedient to the executive and equally hostile to moderate and radical left-wing opposition.

The February revolution deposed the Tzar but maintained some political diversity through the provisional government that sought to bridge divides, but the October revolution liquidated him and his family – along with political diversity.

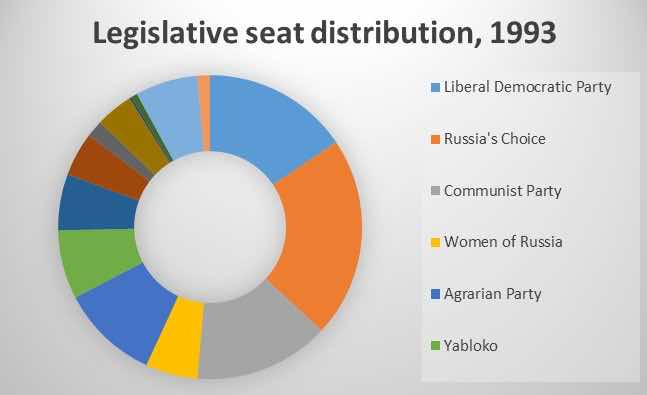

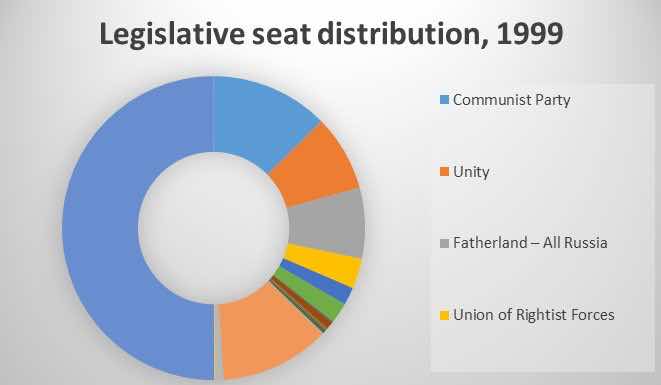

Akin to 1905, the end of the Soviet Union provided another opportunity to create a system of political openness and competition. The first legislative body elected in 1993 was relatively diverse, as seen below.

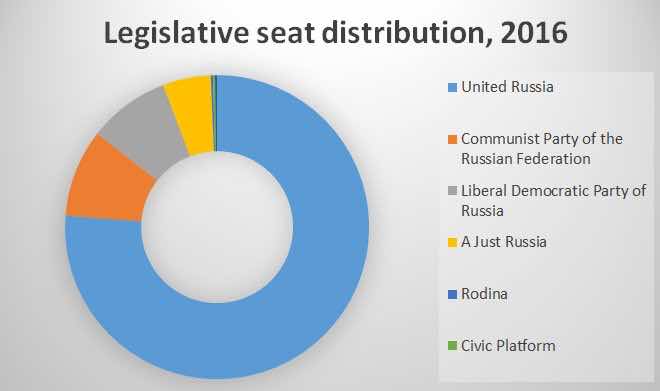

By the end of the decade, antipathy towards Boris Yeltsin had produced an authentic opposition party in the last legislature prior to Putin’s rise to power. Yet in the legislature elected in 2016, not only did United Russia have a veto-proof majority, each of the three “systemic” opposition parties are led by individuals who have pledged loyalty to Putin – leaving non-mainstream parties and movements from the left and right to take to the street.

As in the period leading up to the February and October Revolutions in 1917, Russian society today has relatively little ability to constrain the leadership through its elected representatives. The foreign policy expansion of Russia over the past decade has accordingly proceeded with relatively little input from the legislature. Social conflicts are managed through populism, strident patriotism, and coercion, reducing the influence of moderate voices and opening the door to more extreme outcomes – at home and abroad.