How India tries to benefit from demography via data

Does India have a demographic dividend? That is, does it have many young people of working age who will boost its economy for years to come, or does it have a growing problem of an ageing population?

Does it have a highly-skilled population that will make it the natural hub for technologies like artificial intelligence in the future, building from its current information technology prowess, or will it be home to millions of youth seeking desperately both education and jobs?

The answer, as the English Nobel laureate and writer Rudyard Kipling once said about India, is both true and untrue. It all depends on where you are looking.

The truth is that the situation is varied, unsurprisingly, in one of the most diverse countries in the world. Some parts of India, especially in the south and the west, have low fertility rates, whereas some states in the north and east have very high fertility rates. The trouble is that it is the states that have low fertility rates (like Tamil Nadu and Gujarat) that are some of the most prosperous, industrious and wealthy in India, while in states in the north and east like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, impoverished and ridden with sectarian violence, the fertility levels remain very high. In the states where the fertility levels and poverty remain high, more than half of the women receive little or no education. The men from these areas, often, fare no better.

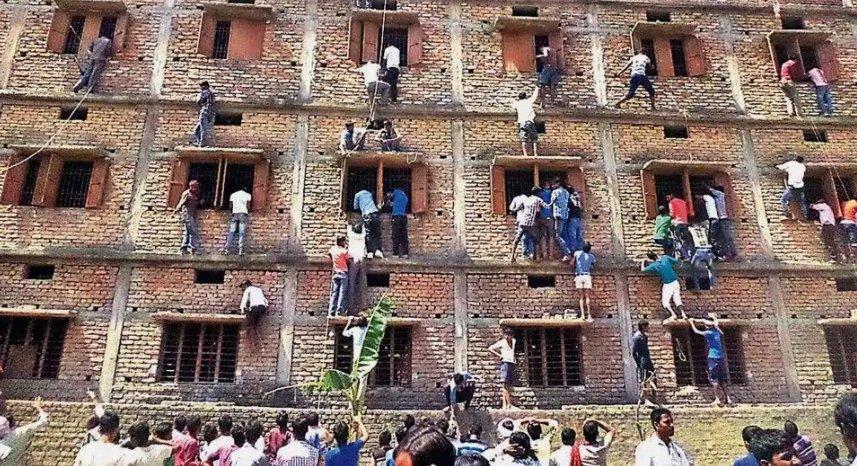

India, thus, has millions of young people, especially men, coming from poor regions who have had little education and possess few high-quality marketable skills. When it makes headlines that millions of young men apply for a few thousand jobs, these are the men who apply for them. It so happens that they are also born in areas where the primary school and collegiate system is nearly destroyed and outrageously corrupt. For instance, a crackdown on cheating, in 2018, on a major final examination in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous region, led to a million students refusing to take it – so pervasive is the corruption that they cannot comprehend an examination in which they cannot cheat. With little education and no skills, all they can comprehend is a clerical government job that would be guaranteed for a lifetime and require little or no expertise.

Despite such challenges, India might still leapfrog on its demographic dividend for two reasons. The first, as the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) has pointed out, is the sheer amount of time that India is likely to retain a youthful population. At present, around 8% of India’s population is over 60 years of age and 30% are at the age of 14 years or below. Around 62.5% of Indians are aged between 15 and 59 years, the working age, and this spread ensures that India will have a demographic advantage all the way to 2055.

The use of mobile data at the grassroots is having a transformative impact. By the end of 2018, Indians had made more than 620 million transactions of more than Rs. 1 trillion (around $15 billion) using internet enabled devices. In 2018 alone, the volume of transactions grew from 150 million to 620 million.

A troika of government schemes to use an identity number for all Indians, to have more bank accounts than ever before cover almost the entire population, and to have in place a digital payments system is triggering entrepreneurial possibilities even in the most mofussil and infrastructure deprived areas of India. Data costs have fallen by 93% in the last three years, making data in India one of the cheapest in the world.

There is only one other country that rolls out tech at this scale – China. India is getting there. According to the EY FinTech Adoption Index, China leads with 69% whereas India is number two at 52%.

All of this means that India’s demographic dividend might come in ways that most people do not imagine. It will not come, now it is clear, through the mass market manufacturing that helped China grow. From land to bureaucratic red-tape, there are still too many hurdles in India. But the transformation might come through the potent mix of a wide and cheap use of data and the power of freedom of speech and expression and democracy – at least this is the alchemy India is betting on. It cannot provide government jobs for the millions of citizens who want them, but it can enable them to dirt-cheap data.