Germany must assume more leadership on global economic issues

German complacency on issues of international and domestic economic management is becoming a threat to the country’s economic future and to containing tensions in trade caused by the rise of China in the East and of populism in the West. The most urgent priority is to address China’s mercantilist challenge to the global trade system embodied in the World Trade Organization (WTO). But Germany’s own economic model, with a foundation in its excellent manufacturing sector and determined fiscal rectitude, is contributing to trade tensions with traditional partners and an inability to meet the growing Chinese challenge. Leadership from Germany, as the most powerful economy in the EU, would benefit both its own economy and the global trading system.

The fundamental structures of the German economy are well known but it is worth updating the description for the 21st century environment. It is heavily dependent on manufacturing.

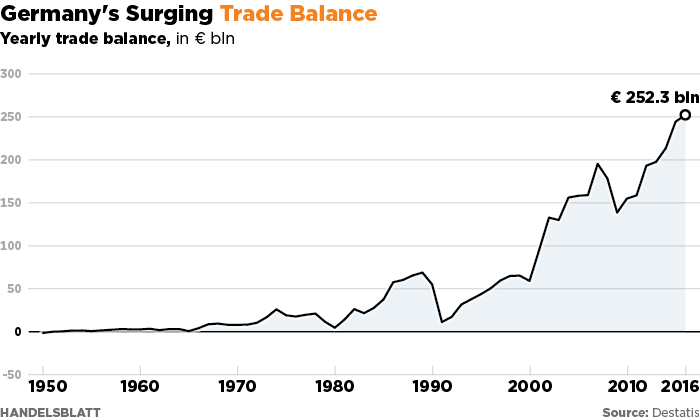

82% of its exports are in manufactured goods, and it enjoys a trade surplus over $400 billion, or around 8% of GDP. Manufacturing wages are high, but so is productivity in the industrial sector. Its output per worker vies with the United States and France among the highest in the world. However, Germany lags in many of the newer technology industries. It continues to train an excellent manufacturing workforce, but only about 3% of its college graduates are in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields, and only 28% of its labor force graduates college. Comparable numbers in the United States are 33% in STEM fields and 42% receiving college degrees. China, Korea and Japan, among others, are producing millions of engineers and scientists each year, although some of those lack the rigor of German or American training. None of Germany’s universities rank in the top 50 in the world. Its services sector, which is increasingly a source of high value added when linked with manufacturing, lags in productivity and global competitiveness. Eighty-six of its R&D is in manufacturing fields, and its venture capital industry is weak. Investment in Germany’s traditionally world-class infrastructure and primary and secondary education also trails competitors like China and Korea.

German savings in the government, corporate and personal sectors are high. Consumption and investment are commensurately lower by 21st century industrial country standards.

Part of the explanation given by federal authorities is the need to save for an aging population and to support research and investment by family-owned, Mittelstand, firms. High savings, however, contribute to the outsized trade surplus, to the slowly deteriorating infrastructure, and to lack of dynamism in creating technologies of the future. Germany’s vaunted “Indstrie 4.0” program devotes well under half a billion dollars to research on manufacturing industries of the future, and almost none to the services sector. This can be contrasted to the hundreds of billions of dollars China is devoting to developing industries such as robotics, 3D printing, semiconductors, biotechnology and electric vehicles.

The newly aggressive Chinese mercantilist “Made in China 2025” and expansionist “One Belt, One Road” programs are the most important threats to the manufacturing-dependent German economy.

The most obvious example is the automobile sector, the traditional source of German economic might and export prowess. Germany exports around half a million vehicles to China and produces and sells almost five million units in China. Yet China’s stated objective is to dominate its domestic market and move rapidly to an all-electric fleet. It aspires to control 80% of its domestic “new energy” vehicle market by 2025. China also has the ambition, and is devoting the resources, to displace German heavy machinery, robotics, and medical device industries. China is becoming competitive in telecommunications, 3D printing, financial services software, quantum computing and industry process software. It is using its vast domestic market and new cybersecurity and data localization laws to hoard the big data needed to perfect artificial intelligence algorithms. Foreign firms are materially disadvantaged by requirements such as forced technology transfer, data localization requirements, competition with state-owned firms, and illicit acquisition of technology. Beijing helps direct, and often finance, purchase of Western technology firms, such as Kuka in Germany, to advance its agenda. Added to this arsenal of tools is the Belt and Road initiative aimed at building the infrastructure to expand exports of Chinese goods and services. Local investment in infrastructure, such as in Eastern Europe, are then leveraged to exert political support for Chinese economic and political ambitions.

The rise of populist and anti-globalization parties and policies in Europe and the United States is also a threat to the global system so crucial to German economic success.

Exports account for over half of GDP for Germany and, as a matter of simple economics, the resulting trade surplus cannot be sustained. Thomas Piketty commented recently on the German exported-oriented economy: “There is quite simply no example in economic history (…) of a country this size which has experienced a comparable level of trade surplus on a long term basis (not even China and Japan which in most instances have not risen above 2-3% in trade surplus).” Former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke emphasizes the political impact of the chronic trade surplus: “What is a problem (…) is that Germany has effectively chosen to rely on foreign rather than domestic demand to ensure full employment at home. (…) Within a fixed exchange-rate system like the Euro currency area, such imbalances are unhealthy, reducing demand and growth in trading partners and generating potentially destabilizing financial flows.”

Political reaction within Europe is often muted due to the importance of Germany to the Union, but the European Commission has frequently suggested policies to reduce the German trade surplus.

The persistent large surplus violates the EU standard for maintaining trade account imbalances below 3% of GDP. Its trade imbalance also impedes economic convergence in Europe. Populist parties have not directly targeted the German trade surplus, rather the perceived negative impact of globalization and the abysmal growth rates and job openings (especially in Southern Europe) linked to trade imbalances. The populist Donald Trump is not so measured and has railed against the German trade surplus repeatedly, especially targeting the auto sector which is vulnerable due to the emissions scandal. Germany also makes a regular appearance on the “watch list” published annually by the US Treasury as part of its report on currency manipulation and its impact on trade.

Germany should address all these simmering issues with an integrated package of trade and macroeconomic policies. In doing so, it would reassert its position, held consistently in the 1980s and 1990s, as a leading supporter and architect of what has been labeled the liberal economic order.

First, following in part recommendations of the European Commission, Germany should put in place macroeconomic reforms to increase investment, make the tax regime more supportive of labor participation and to consumer spending, and strengthen the services sector. Germany will also need to make its corporate tax reform more competitive in the wake of US reforms in 2017. Reforms should be in part supportive of greater investment, as were the U S corporate reforms. Specific ideas to revitalize services include deregulation of professional licensing and business formation rules; greater emphasis in the “Industrie 4.0” program for manufacturing-related services; improving educational opportunities for students in software, technology and financial services skills; programs to aid women entering the workforce; and strengthening the balance sheets of banks. Completing the glacially slow WTO negotiations on services under EU leadership might also bring more efficiency through greater competition.

Second, changing incentives in the tax regime which incentivizes savings and tends to discourage consumption and work would contribute to lowering the trade imbalance and rewarding workers. The share of national income going to labor has declined in recent decades from 65% to 60% due to a variety of policies, including the Haartz reforms.

Third, to maintain its position as a manufacturing and high technology leader, Germany needs to invest more in education, basic research and infrastructure. More investment and consumption are keys to normalize the trade account.

Fourth, Germany should lead the EU in finding ways to meet the Chinese mercantilist challenge. The United States, Japan, South Korea, Australia and many other nations are all affected by the Chinese leap into advanced technology industries. The size and scope of the Chinese effort requires cooperation among like-minded industrial powers to be effective. Efforts should be focused on WTO measures to counter the most obvious Chinese contraventions of its rules: forced technology transfer, abuse of intellectual property rights, subsidization of industry, state involvement (licit or illicit) in acquisition of key technologies of the future, transparency, and restrictions on data flows both internally and across borders. Coordinated efforts to prevent acquisition of sensitive defense and cyber-security technologies and software through investment screening programs are all part of a concerted effort to achieve WTO-compliant and reciprocal actions in the face of Chinese mercantilism. Reform of WTO rules to better address the Chinese threat from state-owned enterprises, subsidization and transparency would also be useful fields for international cooperation.

President Trump in March called the Chinese bluff and began the process of imposing tariffs on steel and (prospectively) on $50 billion worth of technology products allegedly produced with illicitly acquired foreign technology. In April, Trump floated the idea of tariffs on another $100 billion of Chinese imports. Germany has implicitly admitted the need for the steel action by helping organize an EU safeguard measure on steel. It ought to sustain its initial support the U S action on technology transfer in the WTO. This would signal willingness to build the type of international resolve on Chinese mercantilism signaled by the Malmstrom-Seko-Lighthizer statement last December.

Domestic reform to strengthen German competitiveness is part of an integrated program to meet the Chinese challenge and might also help reduce the trade tensions resulting from the chronic trade surplus by increasing domestic demand and investment. Cooperation with like-minded allies, including the United States, would also help rebuild confidence in the global trade and economic order under threat from populism. Building new competitiveness and improving labor participation and compensation are effective means to counter the rise of populism driven by economic complacency and underperformance.