A French Processing Centre in Niger: The first step towards extraterritorial processing of asylum claims or (just) good old resettlement?

When The New York Times made headlines in the migration world with its recent article “At French Outpost in African Migrant Hub, Asylum for a Select Few” about the French refugee agency’s role in the UNHCR humanitarian evacuation scheme, it was not long before the magical concept of “extraterritorial processing” resurfaced. Mostly defined as the processing of asylum requests outside the country of destination, this proposal, repeatedly raised by European Union member states and academics alike since the beginning of the 2000s, has regularly been turned down by EU officials as being mere politically-driven hot air. Often confused with resettlement or other legal access channels, it has been praised as the panacea of the migration and asylum challenges by some, while being criticized as outsourcing and shady responsibility shifting by others.

Since in 2012 the Swiss Federal Assembly amended the Asylum Act, abolishing the possibility of submitting asylum applications to Swiss embassies, even the last door to Europe was shut. The few other existing legal entry schemes are of great value, but have so far been of minor impact if compared to the overall phenomena. In an era of increasingly mixed flows, this closing down of the EU’s external borders, together with the requirement to be in EU territory to access asylum, has resulted in giving those in search of international protection virtually no other choice than to enter European territory irregularly.

But today we might be at a turning point. Indeed, if there is one advantage to the decrease of numbers along the Central Mediterranean Route since the second half of 2017 mainly due to Italy’s (questionable) bilateral agreements with key transit countries, it is that the times might finally be mature for a reasoned discussion on legal pathways. While the Italian private humanitarian corridor mechanism had already set a positive example,[1] it was in September 2017 that the Commission called for a 40,000 places strong resettlement scheme, addressing refugees along the Central Mediterranean Route.

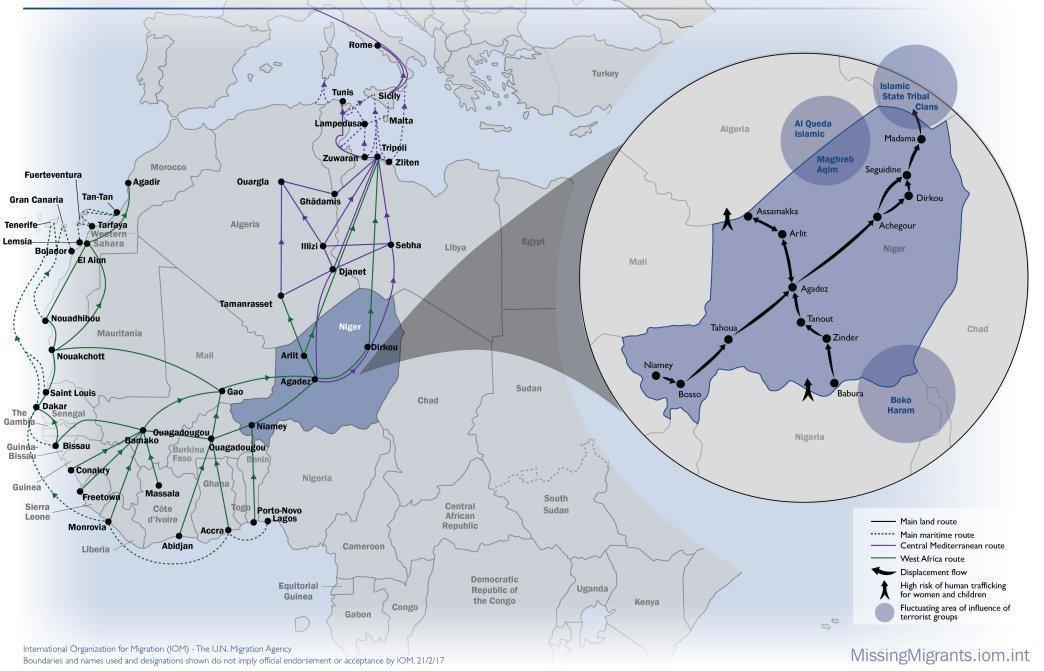

Migration routes crossing Niger

The opening of a transit and departure facility in Tripoli by Libyan authorities with the support of the Italian government followed in late 2017, most likely also in an attempt to address the numerous condemnations of the humanitarian situation in Libya as well as Italy’s and the EU’s role in it. The facility has the capacity to host around 1,000 vulnerable potential refugees identified by the UNHCR who are then either flown out to Rome after a selection by the Italian embassy in Libya,[2] or (as is the case for most) evacuated to Niger before then being resettled to EU member states that have pledged available places. The evacuation targets “extremely vulnerable persons of concern”, such as unaccompanied minors (30%), single mothers, women at risk and torture victims.

While the first evacuations to Niger set off in November 2017 and gained pace in February 2018, current stalling of resettlements from Niger to Europe is overburdening local reception capacities. This is resulting in mounting uneasiness of the Nigerien government, which had only agreed to the plan as it was promised swift procedures of a maximum of a few weeks before the resettlement to the EU. Nevertheless, in practice only 25 resettlements have been operated to France so far, leaving the UNHCR calling for the deployment of further EU resettlement missions and a speeding up of procedures. This stall resulted first in a slowing down of the evacuations from Libya: the 1,300 target goal set by the UNHCR for the end of January has only recently been reached, with 1,342 evacuated by 16 March 2018. Currently the evacuations are completely halted.

The French refugee agency Ofpra is the first that has started playing an active role on the ground. Following French President Emmanuel Macron’s reasoning that “if the Ofpra doesn’t move to Africa to assess the claims of asylum seekers, they will take the journey to Europe”, it begun selecting individuals under the 3,000 resettlement places it pledged to put into place by the end of 2019. But while Macron’s statement might sound as the opening of a new chapter, in practice France (simply) operates a second-stage verification before physically transferring positive resettlement cases.

Indeed, as confirmed by a former high-level UNHCR staff member, a double-interview has been the rule in any case of resettlement during the past 20-30 years. Destination country resettlement missions that pursue an additional interview, including both an element of status determination and security, have indeed been a long-standing practice.[3] Furthermore, due to the conditions in Libya, the UNHCR cannot operate fully-fledged status determination procedures on the ground, and therefore merely engages in the preliminary screening of vulnerabilities of individuals already originating from a restricted set of nationalities.[4]

In short, while the experience of the UNHCR humanitarian evacuation scheme represents a significant step forward by targeting the most vulnerable along the busiest route to Europe, it is unfortunately also a further confirmation of the continuing lack of a common EU policy concerning legal pathways, and thus, and of strong reliance upon individual member states’ efforts. The significant delays and difficulties in the implementation of resettlement pledges recall the experience of past calls for EU resettlement schemes: since July 2015 to today, a total of 29,314 resettlements to Europe have taken place, making it approximately one resettlement daily per destination country.

It is nevertheless undeniable that evacuations from Libya are a necessity: routine (indefinite) detention and inhumane treatment are well-documented common practices, whereas there is no sign that the numbers of persons in need of humanitarian assistance inside Libya have decreased. The International Organization for Migration estimates that there could be up to one million migrants in Libya. In 2017, of the 17,000 detainees registered in official Libyan detention centers, the UNCHR managed to evacuate only 1,000 people and to ask for the release of another 2,000.

These numbers display how this praiseworthy initiative so far represents a drop in the ocean and urgently needs to be stepped up. It is also to be hoped that, when taking one step ahead in developing legal pathways, the EU will not take two steps back in other areas, such as by keeping on supporting the Libyan “coastguard” in the interceptions i.e. condemning migrants to be taken back to exactly those detention centers that the UNHCR is trying to evacuate them from. Policy coherence in external migration policy indeed still seems to have a long way to go.

Footnotes:

[1] Humanitarian corridors are a mechanism of issuing temporary entry visas on humanitarian grounds; it has been implemented in cooperation with religious entities. So far, more than 1,000 vulnerable individuals have arrived from Lebanon since 2016. The protocol will be repeated in 2018, with another 1,000 places pledged. Another 500 will be transferred from Ethiopia (with 139 having already arrived), bringing the total number to 2,500 by the end of 2018.

[2] Already 312 individuals have been transferred from Tripoli to Rome on two flights organised by the Italian authorities in cooperation with religious entities (CIE, Caritas).

[3] Interview of the author with a former UNHCR staff member.

[4] The agreement between UNHCR and Libyan authorities foresees the taking into consideration of merely 7 nationalities, being Syrian, Iraqi, Palestinian, Somali, Eritrean, Oromo Ethiopians and Darfur-originating Sudanese.

Read also:

Italy’s new policy on migration from Libya: will it last?

Mattia Toaldo

Ebook – Beyond the migration and asylum crisis – Options and lessons for Europe