Digital power and democracy

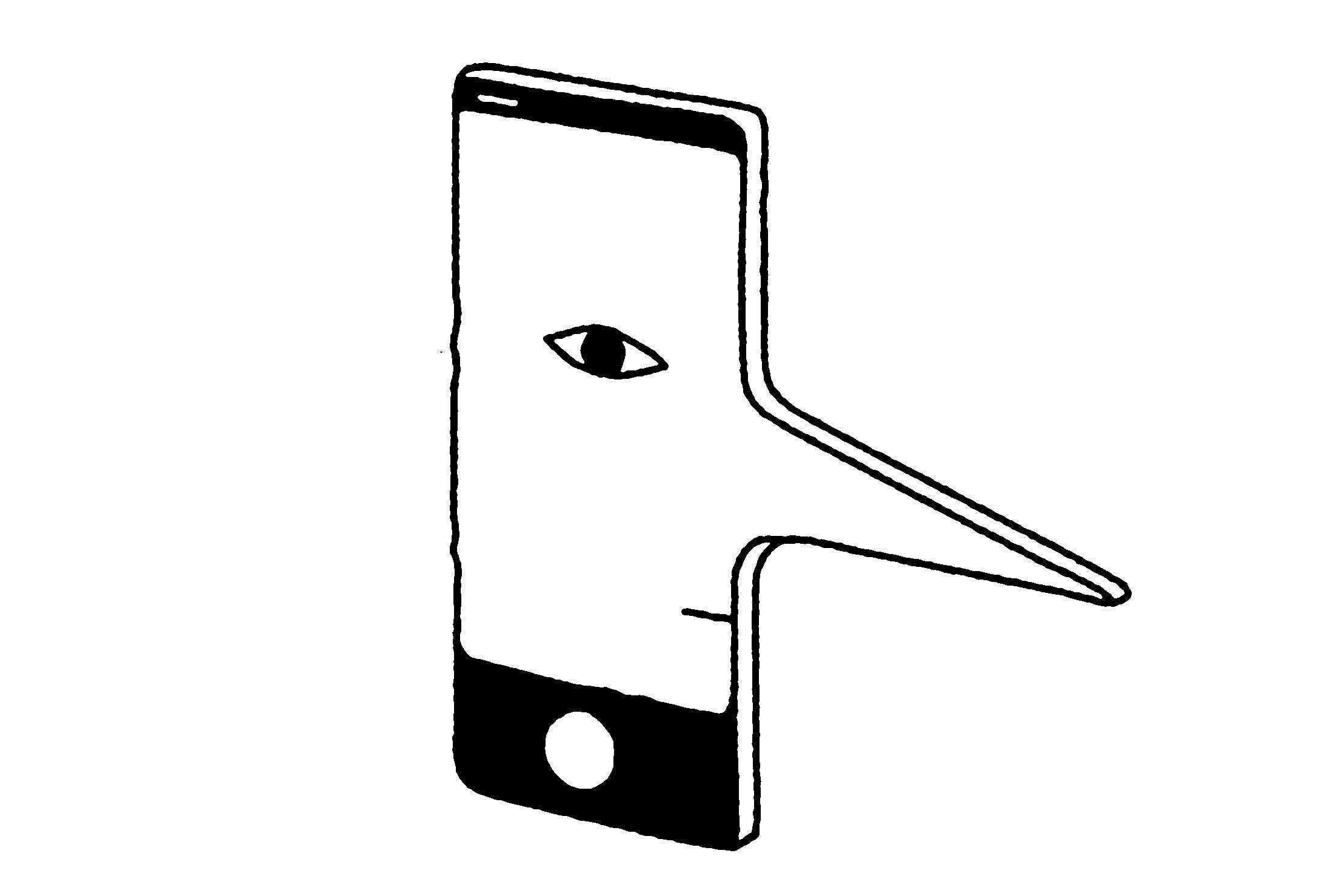

We live in a society that revolves around data. The use of digital data is so all-pervasive, particularly (though not only) in the more industrially-advanced economies, that it has spawned a new ecosystem: the uninterrupted flow of digital information that is growing exponentially is having a major impact on our daily lives and, at this juncture, even on politics. We are living in a kind of “infocracy”, but is it an exaggeration to fear for the future of democracy? The question certainly is not whimsical if we consider the firepower of the “giants” that rake in huge profits from all their various kinds of online business and that, in so doing, have built up an oligopolistic position for themselves.

Part of the problem is a product of the sensitive enmeshment of information and decision-making processes. The citizen-voter – at once consumer, producer and user in the broadest sense of the term – is caught in the crossfire. If citizens are to be an effective factor in overseeing and endorsing the selection of leaders and their decisions, then they also need to be thoroughly informed as voters. And it follows that how they acquire their information is of crucial importance.

VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL: HOW DEMOCRACY IS CHANGING. Specialization and expertise are now disputed, to a certain extent, thanks to immediate, widespread access to a huge mass of more or less raw data and information. Disputing expertise also means attacking the very concept of the division of labor on which market systems are based. If everyone thinks that they can address a highly technical and specific issue with the skill of an “expert”, then the consequence is that any opinion, belief or hypothesis on the macro-economy, vaccines or even black holes and the galaxy acquires equal dignity. And the trend in that direction is extremely strong due to the combined effect of technological factors (such as the digital explosion) and of social and cultural factors (such as growing disenchantment with elites of every kind).

The underlying reason behind this trend – disenchantment with elites and criticism of any kind of expertise – is that the sociocultural escalator allowing for turnover (that is, for access to those elites) is widely perceived as having ground to a halt. Elites are select and highly selective groups, by definition, and today, in fact, they are frequently rechristened “castes”. This is given a negative connotation inasmuch as they are seen as an unfair, self-obsessed closed shop that is virtually unchanging and even hereditary. In short, it implies the very negation of the ever-moving escalator, with its impact on social mobility; and the stability of contemporary democracy has rested on that social mobility for decades.

On a broader level, it is the very notion of meritocracy that is being called into question. Not just the circuit of technical skills supporting political and administrative decisions, but even the very functioning of the democratic mechanism is being fouled up. We can see this both in the impossible debate between experts and the man in the street and in the yawning chasm between the establishment (“professional politicians”) and the rest of society. To put it in a nutshell: liberal democracy is a system based on vertical representation, while infocracy is a horizontal system.

There is a very close link between competence/expertise and democracy, between democratic procedures and a vibrant society as a positive value (rather than a swindle). That link has snapped, and the resulting rift has bred resentment, anger and polarization. Those feelings, in turn, feed daily (often digitally) on incommunicability and on mutual mistrust among various sectors of society, turning them into individual watertight compartments. Each individual forms his own circle, turning it into an impermeable “bubble”. That bubble is then constantly bolstered, with information selected specifically to confirm his or her existing convictions. Society is being molded into tribes; its groups are no longer fluid, identities are becoming exclusive.

The new way of accessing data and information (the ubiquitous web) is speeding this whole process up and causing it to grow in intensity, accelerating centrifugal thrusts and fragmentation. The mechanism is also self-feeding thanks to the “confirmation bias”; it is becoming increasingly difficult to envision a form of civic coexistence that fosters mutual trust and the amenability to compromise. What solidarity there still exists among individuals – which is very important in order to limit damage, especially at times of trouble or of recession – tends to be seen only within those subgroups into which society has now segmented.

THIS FAKE WORLD. The mistrust generated by “fake news” strengthens the two simultaneous effects that represent the crisis in democracy (the crisis in democratic politics) and the technocracy crisis (the lack of skills needed to manage democracy in complex societies, or the crisis in policy). The attack is devastating because it strikes both pillars of contemporary governance.

On the other hand, today’s democracies are not simply electoral machines or mechanisms for political and parliamentary debate. They are also systems which are at once liberal and market-based. While acknowledging the negative impact of political polarization and fragmentation, citizens also need to be able to claim the right to their own “cognitive bubble”; at the end of the day, after all, that is part and parcel of their right to privacy. Choosing our own circle of friends, acquaintances and sources of information is a freedom that we take for granted. There is a thin red line separating obtuse prejudice from a right to form our own community, based on elective affinity. In other words, we cannot forget that even the smallest communities – bound by common interests or by shared opinions – are the salt of democracy. They are not unlike the famous “intermediate bodies” identified by Alexis de Tocqueville in the vibrant American society of a different age (indeed, of a different America).

The trouble is that the search for a direct and hyper-participatory form of democracy (the legendary “web” in place of the normal liberal democratic processes) is not producing encouraging results in terms of policy. It is true – as claimed by those who root for the “street” over the “castle” of representative democracy – that even back in the days of the Athenian “polis” its members held public office in rapid rotation; however, the political system of that era had a small community – a city-state – to run, not the huge, complex and hyperconnected structure of twenty-first century society.

There does not appear to be such a thing as a perfect election system. Direct democracy has numerous drawbacks, on the practical level if nothing else. However, disenchantment with a specific election law or even with an entire political class is not a good reason for jettisoning outright the complex decision-making processes required for managing complex issues.

For a start, in addition to the unquestioned responsibilities incumbent upon those elected (or otherwise appointed) to public office, we might shine the spotlight with greater emphasis on the responsibility of citizens to safeguard the functionality of modern democracy. Along with our right to vote, we have a basic duty to be informed at the very least about the broad outlines of the decisions our leaders are called upon to make. The absence of an “imperative mandate” in the selection of representatives remains a key factor in the democratic process, to some extent divorcing the voter’s choice from the course of action that the person elected then pursues. But it does not seem logical to attack the political “caste” after voting for it, nor indeed to dispute its decisions after opting not to vote at all.

Moreover, certain citizens need to be more responsible and better informed than others. We are talking about professionals in the sphere of communications. Their job does not consist in supplying mere “data” (in today’s world, that basically means digital feeds), but it entails providing “news” and the tools for interpreting that news. This difficult task demands the ability to tell a story and to set that story in some kind of context. For instance, the “posts” in any online chat appear to have a sequential story behind them, but in fact they are all set in a kind of eternal present. Therefore, they are particularly vulnerable to being taken out of context. The more the mainstream media forgoes its duty to tell a story, the more its operators shirk their primary role as a social adhesive or as a mediator of daily experience and of the “shared sense” of reality. In fact this process appears to have been going on for some time now, judging by the frequency with which the mainstream media resorts to the “social media” without bothering to mediate at all.

Admittedly, it is difficult to find one’s way around the hyperconnected universe – never mind helping others to find theirs. It is tempting, obviously, to allow oneself to go with the flow, to accompany it and to follow it. But if one of the purposes of “creating information” is to produce analysis that can facilitate comprehension (possibly even to prepare oneself for future events), then a further and rather different effort needs to be made: as the sociologist Douglas Rushkoff has suggested, when you are immersed in Big Data, the important thing is not to see a lot but to see clearly. You need to identify recurring patterns and to distinguish the “signal” from the “noise”. And doing that is not just a technique, it is an art. Basically, the professional journalist or thinker occasionally needs to tell his “users” that they are wrong, that they are misreading the data or at least not comprehending it completely – and such an operation demands courage.

THE DATA LORDS. A crisis, or at least a partial crisis, in modern democracy has actually been in the air since long before the “new media” arrived on the scene. One could argue that this system for governing civic coexistence showed up for its appointment with the digital revolution already weary and weakened. The underlying problem for liberal market democracies – likely the most accurate definition and the one we should always use – is that of the growing expectations held by the generations born after the second world war. These expectations are at once economic, social and cultural; they have spawned a kind of widespread hedonism followed by a genuinely collective shock in the face of slumping growth forecasts. The so-called “J Curve”, theorized by James Davies in the late 1960s, describes the exact moment of greatest risk for the political stability of democracies: this occurs in already affluent societies when promises are not kept. We have been experiencing a phase of that nature since 2008 at the very least.

This phase has been accompanied by a collapse in people’s confidence in the democratic institutions as tools of social justice, giving modern democracy the aspect of an empty shell. As Zygmunt Bauman wrote, for example, we have witnessed a divorce between power and politics: “real” power appears to have migrated toward non-representative organizations and figures over which we have no control. It is against this backdrop that we need to consider the new forms of power based on communication and information, also in relation to public decision-making.

The “data market” has become a crucial factor in the modern economy and it is paying the price for an unresolved inconsistency: social media operates in a kind of public space that is by its very nature open and apparently free, originally devoid of any ground rules or boundary markers. At the same time, however, social media has evolved in the pursuit of profit (thus within a private, business-based rationale) to the point where its leaders/innovators have turned into oligopolistic, financial giants. This tension – clear for all to see today – is making it that much harder to find solutions to the social problems caused (albeit probably not deliberately) by the growing use of these new forms of digital interaction. Unless the business model changes, it is going to be more and more difficult to prevent citizen-users from increasingly turning into unwitting suppliers of commercial data.

Or worse. “Financial Times” columnist John Gapper draws a parallel between those who take advantage of the social media for illegal, or at least immoral, ends and those who soil a public park or threaten children in a public playground. Free, unfiltered access creates a network of contacts that can be extremely useful for constructive purposes. But that network can also be very vulnerable, especially as it lacks the normal tools of law enforcement that protect the playground, say. So when Mark Zuckerberg voices his astonishment over the “bad guys” disturbing Facebook’s functioning as a large, open platform, it is as though he were voicing his surprise over people betting in a casino. Can the solution be purely technical? Can algorithms become “inspectors”, depersonalizing the defense of the “public” space? Solutions are far from simple. The data lords make it all seem easy, with their manifestos on the world’s future, but the danger, in the end, is that the cure may be almost worse than the disease.

****

The dilemma is unquestionably a factor in daily life on the internet, and thus in the daily lives of a considerable proportion of mankind. But we must not paint a purely static picture of the situation. As in other spheres, so here too are conflicting dynamics at play; there are major oscillations, for example, between common good and private interest, or between phases of major opportunity for “small” players (thanks to the elimination of barriers preventing access) and phases dominated by “big” players (thanks to economies of scale and to the concentration of resources). In short, there is no point in panicking. Technological progress is still a form of progress, though it should not be left to its own devices. And we would all do well to remind ourselves that throughout history, the liberal vision has always had to cope with tension between individual liberty and social order, between the public good and private gain.

*This article is part of Aspenia International, n.80-81